Smudging Through Time

Cleaning with Smoke

Mother nature offers us many plants which have a sweet smell when burned. Around the world, their perfumed smoke has been used to connect with the divine and to dispel negative energy. The plants produce aromatic oils to defend themselves from insects and infections. These oils are present in the smoke, and their anti-microbial powers have been shown by science to kill air-borne diseases.

When I was a child, I loved the smell of incense at the Greek church. It was not until decades later that I learned about this incredible spiritual practice. Like many others of European descent, I was originally reconnected with smoke medicine by Moon Dance grandmothers in Mexico. Thanks to those elders who shared their wisdom with me, I am on a path of discovering my own ancestral smudging story.

Although the practice of smoke medicine barely exists anymore in England, the modern word smudge is actually related to the Middle English word smeche – a smoke produced intentionally or an aromatic smoke. Smudge came to refer to a pile of burning material and eventually the marks produced by touching the ashes became known as smudges.

Historians and scientists often use the term fumigation instead, which comes from the Latin fumare. For centuries it has referred to the use of aromatic smoke for medical treatments, spiritual cleansings and the repelling of insects. That is how the word fumigation came to be associated with pest control.

It is hard to say how early human beings discovered that certain plants created aromatic smoke. We know that by 1825 BCE, in the Kahun Gynecological Papyrus, Egyptian physicians recommended “fumigating her (the patient) with incense and fresh oil, fumigating her womb with it, and fumigating her eyes”.

In the Middle East, fumigation was also a very important medical tool, especially in the treatment of cold and wet conditions. A 3,000 year old Sumerian prescription written on a clay tablet recommends vaginal fumigation with 11 plant residues, for fluids blocked in the womb. Another from the 7th century BCE suggests digging a hole in the ground, adding coals and resins, and having the female patient sit over it.

The same prescription was mentioned a few centuries later by Hippocrates in Ancient Greece and the practice was later documented in Africa by Gustave Witkowski in 1887 as an obstetric practice of sitting over a “pot of fire”. In Ancient Greece they believed that the uterus could move around by itself and that it would be susceptible to different smells. Hippocrates would use sweet smelling smoke to coax the uterus downwards or foul-smelling smoke to chase the uterus back up to its rightful position.

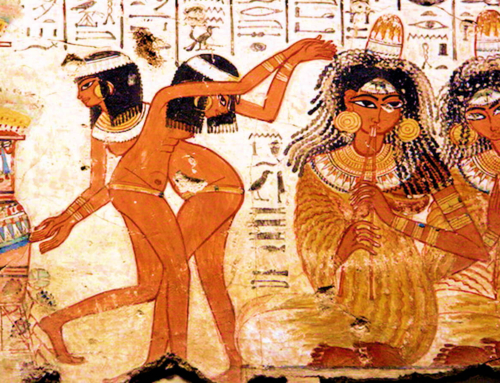

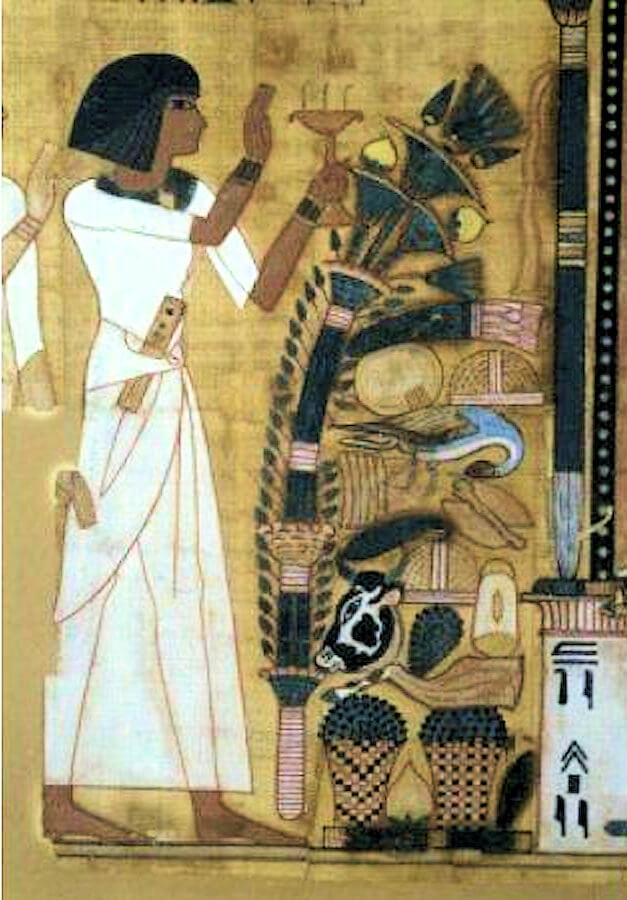

The earliest documentation of smudging for spiritual purposes was the burning of entheogenic plants, whose smoke was used to bring the users closer to the divine through intoxication. The smoke could also be used for communication with ancestors and with the deceased. In 1300 BCE, the Book of the Dead displays the image of the healing goddess Isis performing a ritual fumigation for her dead son. In the bible, incense is associated with the ancient practices of Goddess worship and it is also gifted to the baby Jesus – Frankincense and Myrrh. Although some older churches still use smudging during services, the use of incense as a regular personal practice almost disappeared in Christian households.

Smudging is still practiced in different ways, in many cultures all over the world. In the Americas, as well as other places, people Indigenous to the land have preserved their ancestral smudging practices. Although this practice was criminalized for hundreds of years in the U.S., smoke-based cleansing practices still play an important role in Traditional Native American Medicine. Thanks to the elders who fought to keep them alive, these smudging practices now serve many non-Native people to reconnect with their own ancestral smudging practices.

If you want to use smudging as a wellness tool at home, hopefully you can find a way to revive the ways of your ancestors. If you choose to borrow Native traditions, it is important to respect elders, the rules of rituals, and teaching and sharing protocols. Through research, travel and intuition many people in the modern world are re-connecting with their own sacred practices that may have been lost for hundreds or even thousands of years.